The 16th-century fervently anti-Sunni Iranian Safavid palace and court ‘scholar’, the ‘Shaykh al-Islam’ of Shiism, Majlisi II, not only attacked the Quran by denying its integrity and absolved the Jews of any involvement in the murder of the Prophet (), not only advocated kufr upon kufr in his magnum opus ‘Bihar al-Anwar’ (Bihar al-Dhulamat wal-Khurafat) and other works but also passionately sanctified the Majoosi eid of Nowruz, aligning himself with the ‘Ayatollahs’ in Iran and even Iraq in our time.

The 16th-century fervently anti-Sunni Iranian Safavid palace and court ‘scholar’, the ‘Shaykh al-Islam’ of Shiism, Majlisi II, not only attacked the Quran by denying its integrity and absolved the Jews of any involvement in the murder of the Prophet (), not only advocated kufr upon kufr in his magnum opus ‘Bihar al-Anwar’ (Bihar al-Dhulamat wal-Khurafat) and other works but also passionately sanctified the Majoosi eid of Nowruz, aligning himself with the ‘Ayatollahs’ in Iran and even Iraq in our time.

Category Archives: Persianization of Ahlul-Bayt

The Persian-Zoroastrian Origin Of Excessive Shia Mourning Rituals And Husayn (Siavash) Veneration

Siavash is a prince in the Shahnameh, a legendary Persian prince from the earliest days of the Persian Empire. He was a son of Kay Kavoos, then Shah of Iran, and due to the treason of his stepmother, Soodabeh (with whom he refused to have a relation and betray his father), exiled himself to Turan where he was killed innocently by order of The Turanian king Afrasiab. He was later avenged by his son Kai Khosrau. He is a symbol of innocence in Persian Literature.

The Truth About Nowruz

Nowruz, which literally translates to ‘New Day’ in Persian, marks the beginning of spring. As the spring equinox, Nowruz signals the start of spring in the Northern Hemisphere.

Nowruz, which literally translates to ‘New Day’ in Persian, marks the beginning of spring. As the spring equinox, Nowruz signals the start of spring in the Northern Hemisphere.

Celebrating the commencement of the New Year is one of the oldest observed festivals, with a long history in ancient Mesopotamia before the arrival of the Persian people to the region. It predates Persian civilization and Zoroastrianism, although it later became the greatest religious festival for Zoroastrians. The Sumerians, founders of some of the oldest city-states in ancient Mesopotamia (between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers around 3000 BC, present-day southern Iraq), celebrated their new year by growing barley in the first month of their calendar, which fell in March/April. In fact, their New Year was called The Festival of the Sowing of Barley.

Such celebrations were closely tied in with various gods and goddesses and creation myths popular amongst ancient nations, and involved rites and ceremonies expressing jubilation over life’s renewal, which is the essence of the New Year festivals.

The nomadic Iranic tribes that migrated to what is known as the Iranian plateau copied and adopted many customs, including Semitic scripts, from the ancient civilizations of the Middle East that preceded them. This is a historical fact that is often undermined, if not completely ignored, by Iranian nationalists and supremacists who often perceive themselves as superior to the older civilizations of the Middle East.

Iranian historian (Ph.D.) Khodadad Rezakhani says:

Roots of Nowruz

Nowruz is commonly perceived as the most “Iranian” of all celebrations, emphasising an Aryan/Indo-Iranian root for the celebration. However, the lack of any mention of Nowruz or the traditional, well-known celebrations associated with it in Achaemenid inscriptions as well as the oldest parts of the Avesta, the Old Iranian hymns of Zoroastrianism, can point to the non-Iranian roots of the celebration.

We know that the Sumerian and Babylonian calendars of the Mesopotamia were based on the changing of the seasons. The sedentary agriculture of Mesopotamia that served as the backbone of Babylonian economy greatly depended on the changing of the seasons and the amount of yearly downpour. Subsequently, the beginning of the spring mattered greatly in Mesopotamia and was celebrated accordingly. There also existed an annual ritual in Babylonia when at the beginning of the spring the king was required to make a journey to the temple of Marduk and receive the regal signs from the god and give royal protection to the great god of Babylon. The yearly renewal of this mutual support seems to symbolize the renewal of life marked by the beginning of the spring. We have decisive records of the adoption of this ritual by the Iranians when Cyrus the Great invaded Babylon and appointed his son, Cambyses, as his deputy there.

On the other hand, the life style of Iranian tribes prior to their settlement in Iran was nomadic and greatly depended on cattle raising instead of sedentary agriculture, thus devoid of the need to keep exact track of seasonal change. Their homeland, in the central Asian steppes, possessed either very cold winters or scorching summers and the arrival of spring seldom had the same effect as it does on the more temperate lands to the south.

As a result, it is possible to conclude that the original roots of Nowruz laid in the Mesopotamian celebration of the arrival of spring and was later adopted by settled Iranian tribes, probably as early as the reign of the first Achaemenid emperor. It should be pointed out that if we accept this theory of adoption, we should not forget the certain Iranian characteristics that shaped this celebration into a distinctly Iranian custom.

Reference: https://iranologie.com/the-history-page/nowruz-in-history/

Neo-Assyrian (Semite) iconography is evident in many Persian traditions and historical monuments, such as Persepolis (‘Throne of Jamshid’), the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC), and in pre-Zoroastrian symbols like the winged sun, used by various powers of the Ancient Near East, primarily those of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. The Zoroastrian adoption of the symbol known as the Faravahar has its origins in Semite Neo-Assyrian iconography. This Assyrian image often includes their Tree of Life, featuring the god Ashur on a winged disk.

Ancient Mesopotamian New Year festivals initially influenced the New Year celebration in ancient Iran. However, Nowruz gradually evolved and by the end of the Sasanian period (7th century AD) became uniquely Iranian by incorporating Zoroastrian creation myths and other stories popular during the late Sasanian period. Other Persian festivals like Mehragan, Tirgan, and Yalda are connected to the Sun god (Surya) and originate in Mithraism.

Is Nowruz a mere cultural festival devoid of religious connotations?

It is argued that people from various religious and cultural backgrounds celebrate Nowruz, suggesting it has lost any religious connotation. However, couldn’t the same argument be applied to Christmas or Halloween? Many celebrate Christmas without believing in God, or Halloween without believing in devils.

But is that claim even true?

Let’s take Iran as an example: Nowruz in Iranian culture, which has a significant influence on Nowruz celebrations globally, is rooted in the traditions of Iranian religions such as Mithraism and Zoroastrianism. In Mithraism, festivals were deeply linked to the light of the sun. Iranian festivals such as Mehregan (autumnal equinox), Tirgan, and the eve of Chelle ye Zemestan (winter solstice) also have origins in the worship of the Sun god (Surya). Some argue that Nowruz is not mentioned in primary Zoroastrian scripture.

This is a flawed argument as Nowruz gradually evolved and by the end of the Sasanian period (7th century AD) became uniquely Iranian by incorporating Zoroastrian creation myths and other stories popular during the late Sasanian period.

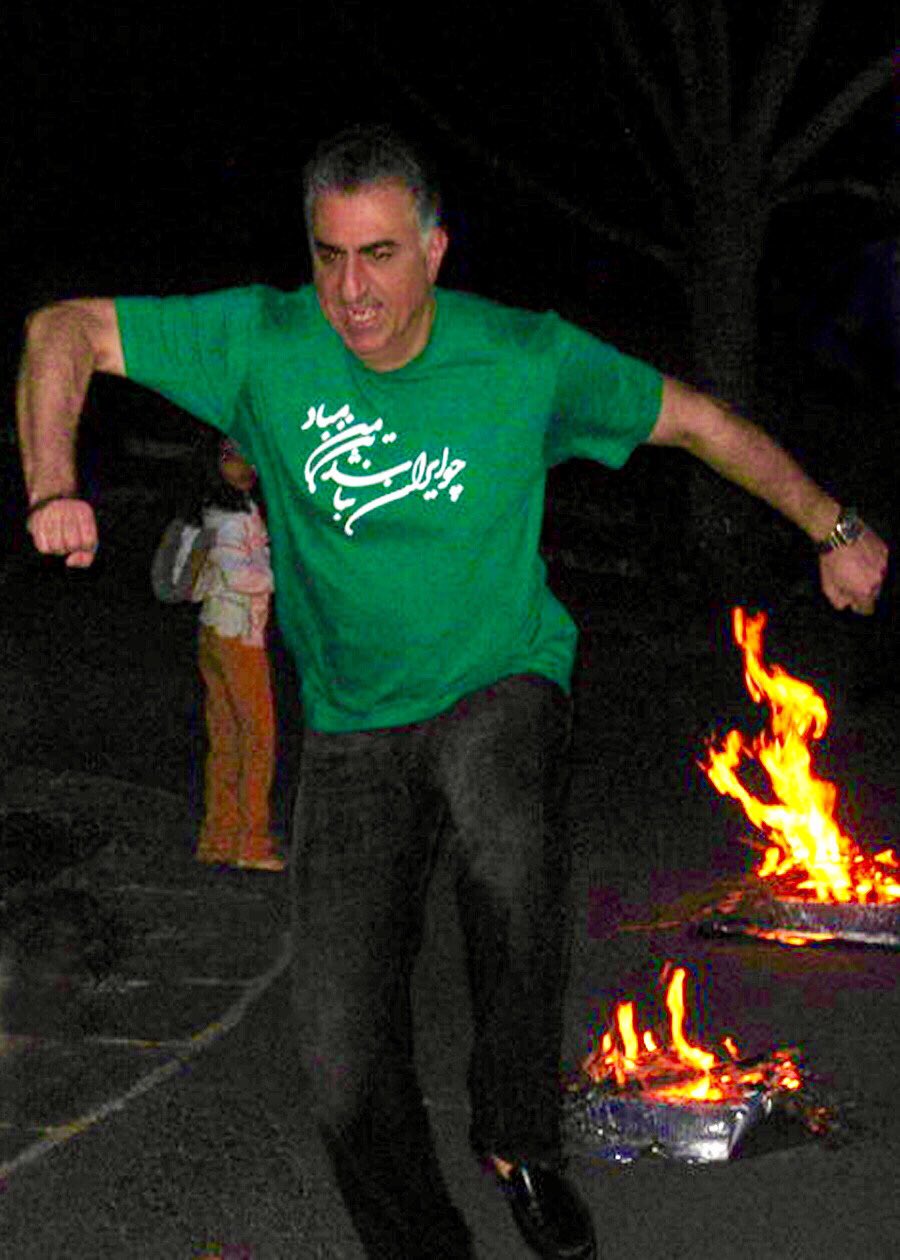

Fire rituals, from Anatolia, Kurdistan to Khorasan

On the eve of Nowruz, in southern and eastern Kurdistan, bonfires are lit. In the Kurdish regions of Turkey, specifically in Eastern Anatolia but also in Istanbul and Ankara where there are large Kurdish populations, people gather and jump over bonfires.

Armenian scholar Mardiros Ananikian (Ananikean, M. H. 2010) emphasizes the identical nature of Nowruz and the Armenian traditional New Year, Navasard, noting that it was only in the 11th century that Navasard came to be celebrated in late summer rather than in early spring. He states that the Nowruz–Navasard “was an agricultural celebration connected with commemoration of the dead […] and aiming at the increase of the rain and the harvests.” The great center of Armenian Navasard, Ananikian points out, was Bhagavan, the centre of fire worship.

Fire rituals hold significant importance in Zoroastrianism. According to Zoroastrian doctrine, fire symbolizes light, goodness, and purification. Angra Mainyu, the demonic antithesis of Zoroastrianism, was challenged by Zoroastrians with a large fire annually, symbolizing their resistance to and disdain for evil and the arch-demon. Hence, from Kurdistan to Khorasan, fire rituals are integral to Nowruz celebrations.

Fire-jumping rituals

Chaharshanbe Suri (Persian: چهارشنبه سوری) is closely related to Nowruz and is a fire-jumping ritual in Iran where people literally seek blessings from fire.

Loosely translated as Wednesday Light, from the word sur which means light in Persian, or more plausibly, consider sur to be a variant of sorkh (red) and take it to refer either to the fire itself or to the ruddiness (sorkhi), meaning good health or ripeness, supposedly obtained by jumping over it is an ancient Iranian festival dating back to at least 1700 BCE of the early Zoroastrian era. Also called the Festival of Fire, it is a prelude to Nowruz, which marks the arrival of spring.

ace-pre-wrap break-words [.text-message+&]:mt-5 overflow-x-auto”>

Ancient Persians celebrated the last 5 days of the year in their annual obligation feast of all souls, Hamaspathmaedaya (Farvardigan or popularly Forodigan). They believed Faravahar, the guardian angels for humans, and also the spirits of the dead would come back for a reunion. There are the seven Amesha Spenta, which are represented as the haft-sin (literally, seven S’s). These spirits were entertained as honored guests in their old homes and were bidden a formal ritual farewell at the dawn of the New Year. The festival also coincided with festivals celebrating the creation of fire and humans. In the Sassanid period, the festival was divided into two distinct pentads, known as the lesser and the greater Pentad, or Panji as it is called today. Gradually the belief developed that the ‘Lesser Panji’ belonged to the souls of children and those who died without sin, whereas ‘Greater Panji’ was truly for all souls.

Bonfires are lit to “keep the sun alive” until early morning. The celebration usually starts in the evening, with people making bonfires in the streets and jumping over them singing

“zardi-ye man az toh, sorkhi-ye toh az man”.

The literal translation is, “My yellow is yours, your red is mine.” This is a purification rite. Loosely translated, this means you want the fire to take your pallor, sickness, and problems and in turn give you redness, warmth, and energy.

Note: Many Zoroastrian priests reject this practice as folly by the uninformed laity.

Nowruz in Kurdistan

In Afghanistan, Nowruz celebrations usually last around two weeks, culminating on the first day of the Afghan New Year, which in Afghanistan will be celebrated on Sunday 21st March. Preparations for Nowruz traditionally start after Chaharshanbe Suri, the festival of fire.

Various superstitious rituals are deeply intertwined with Nowruz celebrations in Afghanistan, predominantly observed by the Shia community, as Nowruz is sanctified by Shia authorities.

On this day, new items are purchased and exchanged as gifts. Children receive toys, and everyone adorns themselves in new clothing. Families visit each other, making it truly an eid in every sense of the word.

Each Nowruz, at the annual Jahenda Bala (Persian/Dari: جهنده بالا) ceremony, a ‘holy’ flag whose color configuration resembles Derafsh Kaviani (the royal standard of Iran used since ancient times until the fall of the Sasanian Empire) is raised in honour of Ali ibn Abi Talib (may Allah be pleased with him. People beseech Ali for aid and help and touch the flag for luck in the New Year.

Nowruz according to Zoroastrianism

The last five days of the last month of the year, called Panjeye Kuchak or “the Small Five,” coincides roughly with March 10-15. During these five days, Zoroastrians take care of the preparatory aspects of Nowruz, including the spring cleaning and buying of new clothes.

Following the Panjeye Kuchak, Zoroastrians believe that the souls of their loved ones and ancestors will return to their homes during the last week of the year, the Panjeye Bozorg, the last five days of the year. Taking care of their spring cleaning before the Panjeye Bozorg reflects one way of welcoming these spirits into their homes

In case some spirits lose their way home, Zoroastrian communities in Yazd and Kerman light fires on their roofs to help guide the fravarhars–the soul that God has bestowed upon humans–descending from the skies on the last night of the Panjeye Bozorg. Some view this as one of the many roots to Chaharshanbe Suri, a holiday where non-Zoroastrian Iranians jump over fire on the last Tuesday night of the year. The relationship might be possible, except that Zoroastrians do not celebrate Chaharshanbe Suri: the Zoroastrian calendar has no “chaharshanbe,” or “Wednesday,” and jumping over fire is seen as disrespectful to fire, which Zoroastrians hold sacred.

Reference: https://ajammc.com/2016/03/21/zoroastrian-nowruz-in-tehran-celebrating-the-big-five/

The Haft Sin

The Zoroastrian-Parsi website http://www.avesta.org states:

The Haft-Sheen table symbolizes the holiday spirit in much the same way the Christmas tree promotes a special festive mood and the table is kept replenished for thirteen days. To the Zoroastrians, the sixth day is called the “Naurooz Bozorg” or “greater Naurooz” as it is celebrated as the birthday of Holy Zarathushtra.

Reference: http://www.avesta.org/afrin/20100321_Naurooz_Prayer_Book_all_52_Pages_Landscape_Final.pdf

Haft-sin or Haft-seen (Persian: هفتسین) is an arrangement of seven symbolic items whose names start with the letter “س” pronounced as “seen” the 15th letter in the Persian alphabet; haft (هفت) is Persian for seven. It is an integral part of Nowruz celebrations in Iran, however, the items vary slightly in different parts of the country, but certain elements define a Haft-Sin. These elements are Sabzeh (wheatgrass grown in a dish), Samanu (sweet pudding made from wheat germ), Senjed (sweet dry fruit of the lotus tree), Serkeh (Persian vinegar), Seeb (apple), Seer (garlic), and Somaq (sumac). As well as these elements, Iranians tend to put other items such as a mirror, candle, colored eggs, a bowl of water with an orange floating in it, goldfish, coins, hyacinth, and traditional sweets and pastries like nokhodchi.

Another important item is a “book of wisdom”, which can be the Avesta, the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, or the divan of Hafiz. Religious Shiites also put the Qur’an and images of their Imams on their Haft Sin table.

When the new year begins, older members of the family open the book and consult the book for a resolution or insight for starting the new year. Besides, this is the moment when elderlies give money to youngsters and children, which is called ‘eidi’. They normally put new banknotes between the pages of the book and as soon as the new year begins, they open it and give the money as a gift to the family members.

The seven motifs originate from Zoroastrian beliefs, with Ahura Mazda co-existing with six other demigods (Izads) who together form a unity of seven. Therefore, it is no surprise that the holiday now centers around setting out a table of seven items, starting with Seen (س), also called ‘Haft Seen’. The true significance of seven was to represent the “Seven Eternal Laws”, embodying the Teachings of Zarathushtra. It served as a way of preserving and reminding of the teachings of Zarathushtra.

The significance of seven runs deep in Zoroastrian belief, particularly with the seven creations and the seven Amesha Spenta. If you’re not familiar with the latter, it’s referring to the seven ‘Holy Immortals’ (demigods, similar to Shia Imams) that together form sort of a Zoroastrian divine heptad composed of the main god, Ahura Mazda, and six lesser deities (sometimes understood as manifestations of the latter) that together are in a sort of unity ruling over the seven creation.

I believe the provided information makes it abundantly clear that Nowruz is not devoid of religious or pagan connotations, at least not according to strict monotheistic Islamic standards. Of course, everyone is free to celebrate as they wish. However, as Muslims, we have our own Eid festivals which we believe to be the greatest and most excellent, not to be overshadowed by any other celebrations.

‘Abdul-Hussain VS ‘Abdul-Massih

السلسلة: #إنهم_مجوس – حقيقة الرافضة الإمامية الوثنية

Continue reading السلسلة: #إنهم_مجوس – حقيقة الرافضة الإمامية الوثنية

Ayatullats: Happy Nowruz!

A young Palestinian student of mine said to me: “Ustadh, I’ve this Shia boy in my class, he said today is Muslim new year. I thought he meant Hijri new year (even that’s a bid’a to celebrate), but his friend told him about Nowruz in the Shia mosque!

Ayatullats = The Culprits Behind The Persianisation of The Ahlul-Bayt

Persianised and whitewashed depections (often strangely effaminate) of the Ahlul-Bayt are widespread in Shia regions of Iran and Iraq and elswhere for a reason. It is not just some ‘cultural practice’ that is shunned by Shia scholars, on the contrary, the Shia scholars have sanctified Catholic-esque iconography and saint depiction with their lax views regarding the depiction of human beings, particularly saints.

Continue reading Ayatullats = The Culprits Behind The Persianisation of The Ahlul-Bayt